Interpreting regression coefficient in R

Want to share your content on R-bloggers? click here if you have a blog, or here if you don't.

Linear models are a very simple statistical techniques and is often (if not always) a useful start for more complex analysis. It is however not so straightforward to understand what the regression coefficient means even in the most simple case when there are no interactions in the model. If we are not only fishing for stars (ie only interested if a coefficient is different for 0 or not) we can get much more information (to my mind) from these regression coefficient than from another widely used technique which is ANOVA. Comparing the respective benefit and drawbacks of both approaches is beyond the scope of this post. Here I would like to explain what each regression coefficient means in a linear model and how we can improve their interpretability following part of the discussion in Schielzeth (2010) Methods in Ecology and Evolution paper.

Let’s make an hypothetical example that will follow us through the post, say that we collected 10 grams of soils at 100 sampling sites, where half of the site were fertilized with Nitrogen and the other half was kept as control. We also used recorded measure of mean spring temperature and annual precipitation from neighboring meteorological stations. We are interested to know how temperature and precipitation affect the biomass of soil micro-organisms, and to look at the effect of nitrogen addition. To keep things simple we do not expect any interaction here.

# let's simulate the data the explanatory variables: temperature (x1), # precipitation (x2) and the treatment (1=Control, 2= N addition) set.seed(1) x1 <- rnorm(100, 10, 2) x2 <- rnorm(100, 100, 10) x3 <- gl(n = 2, k = 50) modmat <- model.matrix(~x1 + x2 + x3, data = data.frame(x1, x2, x3)) # vector of fixed effect betas <- c(10, 2, 0.2, 3) # generate data y <- rnorm(n = 100, mean = modmat %*% betas, sd = 1) # first model m <- lm(y ~ x1 + x2 + x3) summary(m) ## ## Call: ## lm(formula = y ~ x1 + x2 + x3) ## ## Residuals: ## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max ## -2.8805 -0.4948 0.0359 0.7103 2.6669 ## ## Coefficients: ## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|) ## (Intercept) 10.4757 1.2522 8.37 4.8e-13 *** ## x1 2.0102 0.0586 34.33 < 2e-16 *** ## x2 0.1938 0.0111 17.52 < 2e-16 *** ## x32 3.1359 0.2109 14.87 < 2e-16 *** ## --- ## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1 ## ## Residual standard error: 1.05 on 96 degrees of freedom ## Multiple R-squared: 0.949, Adjusted R-squared: 0.947 ## F-statistic: 596 on 3 and 96 DF, p-value: <2e-16

Let’s go through each coefficient: the intercept is the fitted biomass value when temperature and precipitation are both equal to 0 for the Control units. In this context it is relatively meaningless since a site with a precipitation of 0mm is unlikely to occur, we cannot therefore draw further interpretation from this coefficient. Then x1 means that if we hold x2 (precipitation) constant an increase in 1° of temperature lead to an increase of 2mg of soil biomass, this is irrespective of whether we are in the control or nutrient added unit. Similarly x2 means that if we hold x1 (temperature) constant a 1mm increase in precipitation lead to an increase of 0.19mg of soil biomass. Finally x32 is the difference between the control and the nutrient added group when all the other variables are held constant, so if we are at a temperature of 10° and a precipitation of 100mm, adding nutrient to the soil lead to changes from 10+2x10+0.19x100= 49mg to 52mg of soil biomass. Now let’s make a figure of the effect of temperature on soil biomass

plot(y ~ x1, col = rep(c("red", "blue"), each = 50), pch = 16, xlab = "Temperature [°C]",

ylab = "Soil biomass [mg]")

abline(a = coef(m)[1], b = coef(m)[2], lty = 2, lwd = 2, col = "red")

What happened there? It seems as if our model is completely underestimating the y values … Well what we have been drawing is the estimated effect of temperature on soil biomass for the control group and for a precipitation of 0mm, this is not so interesting, instead we might be more interested to look at the effect for average precipitation values:

plot(y ~ x1, col = rep(c("red", "blue"), each = 50), pch = 16, xlab = "Temperature [°C]",

ylab = "Soil biomass [mg]")

abline(a = coef(m)[1] + coef(m)[3] * mean(x2), b = coef(m)[2], lty = 2, lwd = 2,

col = "red")

abline(a = coef(m)[1] + coef(m)[4] + coef(m)[3] * mean(x2), b = coef(m)[2],

lty = 2, lwd = 2, col = "blue")

# averaging effect of the factor variable

abline(a = coef(m)[1] + mean(c(0, coef(m)[4])) + coef(m)[3] * mean(x2), b = coef(m)[2],

lty = 1, lwd = 2)

legend("topleft", legend = c("Control", "N addition"), col = c("red", "blue"),

pch = 16)

Now this look better, the black line is the effect of temperature on soil biomass averaging out the effect of the treatment, it might be of interest if we are only interested in looking at temperature effects.

In this model the intercept did not make much sense, a way to remedy this is to center the explanatory variables, ie removing the mean value from the variables.

# now center the continuous variable to change interpretation of the # intercept data_center <- data.frame(x1 = x1 - mean(x1), x2 = x2 - mean(x2), x3 = x3) modmat <- model.matrix(~x1 + x2 + x3, data = data.frame(x1 = x1, x2 = x2, x3 = x3)) data_center$y_center <- rnorm(n = 100, mean = modmat %*% betas, sd = 1) # second model m_center <- lm(y_center ~ x1 + x2 + x3, data_center) summary(m_center) ## ## Call: ## lm(formula = y_center ~ x1 + x2 + x3, data = data_center) ## ## Residuals: ## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max ## -2.4700 -0.5525 -0.0287 0.6701 1.7920 ## ## Coefficients: ## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|) ## (Intercept) 50.4627 0.1423 354.6 <2e-16 *** ## x1 1.9724 0.0561 35.2 <2e-16 *** ## x2 0.1946 0.0106 18.4 <2e-16 *** ## x32 2.8976 0.2020 14.3 <2e-16 *** ## --- ## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1 ## ## Residual standard error: 1 on 96 degrees of freedom ## Multiple R-squared: 0.951, Adjusted R-squared: 0.949 ## F-statistic: 620 on 3 and 96 DF, p-value: <2e-16

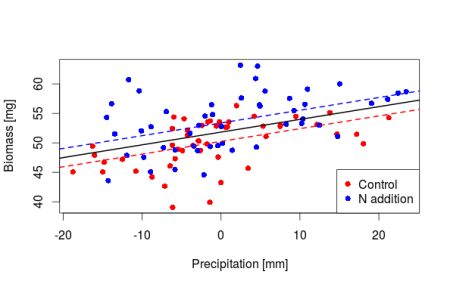

Now through this centering we know that under average temperature and precipitation conditions the soil biomass in the control plot is equal to 50.25mg, in the nitrogen enriched plot we have 53mg of soil biomass. The slopes are not changing we are just shifting where the intercept lie making it directly interpretable. Let’s do a plot

plot(y_center ~ x2, data_center, col = rep(c("red", "blue"), each = 50), pch = 16,

xlab = "Precipitation [mm]", ylab = "Biomass [mg]")

abline(a = coef(m_center)[1], b = coef(m_center)[3], lty = 2, lwd = 2, col = "red")

abline(a = coef(m_center)[1] + coef(m_center)[4], b = coef(m_center)[3], lty = 2,

lwd = 2, col = "blue")

# averaging effect of the factor variable

abline(a = coef(m_center)[1] + mean(c(0, coef(m_center)[4])), b = coef(m_center)[3],

lty = 1, lwd = 2)

legend("bottomright", legend = c("Control", "N addition"), col = c("red", "blue"),

pch = 16)

We might also be interested in knowing which from the temperature or the precipitation as the biggest impact on the soil biomass, from the raw slopes we cannot get this information as variables with low standard deviation will tend to have bigger regression coefficient and variables with high standard deviation will have low regression coefficient. One solution is to derive standardized slopes that are in unit of standard deviation and therefore directly comparable in terms of their strength between continuous variables:

# now if we want to find out which of the two continuous variables as the

# most importance on y we can compute the standardized slopes from the

# unstandardized ones:

std_slope <- function(model, variable) {

return(coef(model)[variable] * (sd(m$model[[variable]])/sd(m$model[[1]])))

}

std_slope(m, "x1")

## x1

## 0.7912

std_slope(m, "x2")

## x2

## 0.4067

From this we can conclude that temperature as a bigger impact on soil biomass than precipitation. If we wanted to compare the continuous variables with the binary variable we could standardize our variables by dividing by two times their standard deviation following Gelman (2008) Statistics in medecine.

Here we saw in a simple linear context how to derive quite a lot of information from our estimated regression coefficient, this understanding can then be apply to more complex models like GLM or GLMM. These models are offering us much more information than just the binary significant/non-significant categorization. Happy coding.

Filed under: R and Stat Tagged: LM, R

R-bloggers.com offers daily e-mail updates about R news and tutorials about learning R and many other topics. Click here if you're looking to post or find an R/data-science job.

Want to share your content on R-bloggers? click here if you have a blog, or here if you don't.