Practical Machine Learning with R and Python – Part 5

Want to share your content on R-bloggers? click here if you have a blog, or here if you don't.

This is the 5th and probably penultimate part of my series on ‘Practical Machine Learning with R and Python’. The earlier parts of this series included

1. Practical Machine Learning with R and Python – Part 1 In this initial post, I touch upon univariate, multivariate, polynomial regression and KNN regression in R and Python

2.Practical Machine Learning with R and Python – Part 2 In this post, I discuss Logistic Regression, KNN classification and cross validation error for both LOOCV and K-Fold in both R and Python

3.Practical Machine Learning with R and Python – Part 3 This post covered ‘feature selection’ in Machine Learning. Specifically I touch best fit, forward fit, backward fit, ridge(L2 regularization) & lasso (L1 regularization). The post includes equivalent code in R and Python.

4.Practical Machine Learning with R and Python – Part 4 In this part I discussed SVMs, Decision Trees, validation, precision recall, and roc curves

This post ‘Practical Machine Learning with R and Python – Part 5’ discusses regression with B-splines, natural splines, smoothing splines, generalized additive models (GAMS), bagging, random forest and boosting

As with my previous posts in this series, this post is largely based on the following 2 MOOC courses

1. Statistical Learning, Prof Trevor Hastie & Prof Robert Tibesherani, Online Stanford

2. Applied Machine Learning in Python Prof Kevyn-Collin Thomson, University Of Michigan, Coursera

You can download this R Markdown file and associated data files from Github at MachineLearning-RandPython-Part5

For this part I have used the data sets from UCI Machine Learning repository(Communities and Crime and Auto MPG)

1. Splines

When performing regression (continuous or logistic) between a target variable and a feature (or a set of features), a single polynomial for the entire range of the data set usually does not perform a good fit.Rather we would need to provide we could fit

regression curves for different section of the data set.

There are several techniques which do this for e.g. piecewise-constant functions, piecewise-linear functions, piecewise-quadratic/cubic/4th order polynomial functions etc. One such set of functions are the cubic splines which fit cubic polynomials to successive sections of the dataset. The points where the cubic splines join, are called ‘knots’.

Since each section has a different cubic spline, there could be discontinuities (or breaks) at these knots. To prevent these discontinuities ‘natural splines’ and ‘smoothing splines’ ensure that the seperate cubic functions have 2nd order continuity at these knots with the adjacent splines. 2nd order continuity implies that the value, 1st order derivative and 2nd order derivative at these knots are equal.

A cubic spline with knots , k=1,2,3,..K is a piece-wise cubic polynomial with continuous derivative up to order 2 at each knot. We can write

.

For each (),

are called ‘basis’ functions, where

,

,

,

where k=1,2,3… K The 1st and 2nd derivatives of cubic splines are continuous at the knots. Hence splines provide a smooth continuous fit to the data by fitting different splines to different sections of the data

1.1a Fit a 4th degree polynomial – R code

In the code below a non-linear function (a 4th order polynomial) is used to fit the data. Usually when we fit a single polynomial to the entire data set the tails of the fit tend to vary a lot particularly if there are fewer points at the ends. Splines help in reducing this variation at the extremities

library(dplyr)

library(ggplot2)

source('RFunctions-1.R')

# Read the data

df=read.csv("auto_mpg.csv",stringsAsFactors = FALSE) # Data from UCI

df1 <- as.data.frame(sapply(df,as.numeric))

#Select specific columns

df2 <- df1 %>% dplyr::select(cylinder,displacement, horsepower,weight, acceleration, year,mpg)

auto <- df2[complete.cases(df2),]

# Fit a 4th degree polynomial

fit=lm(mpg~poly(horsepower,4),data=auto)

#Display a summary of fit

summary(fit)

##

## Call:

## lm(formula = mpg ~ poly(horsepower, 4), data = auto)

##

## Residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -14.8820 -2.5802 -0.1682 2.2100 16.1434

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

## (Intercept) 23.4459 0.2209 106.161 <2e-16 ***

## poly(horsepower, 4)1 -120.1377 4.3727 -27.475 <2e-16 ***

## poly(horsepower, 4)2 44.0895 4.3727 10.083 <2e-16 ***

## poly(horsepower, 4)3 -3.9488 4.3727 -0.903 0.367

## poly(horsepower, 4)4 -5.1878 4.3727 -1.186 0.236

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## Residual standard error: 4.373 on 387 degrees of freedom

## Multiple R-squared: 0.6893, Adjusted R-squared: 0.6861

## F-statistic: 214.7 on 4 and 387 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-16

#Get the range of horsepower

hp <- range(auto$horsepower)

#Create a sequence to be used for plotting

hpGrid <- seq(hp[1],hp[2],by=10)

#Predict for these values of horsepower. Set Standard error as TRUE

pred=predict(fit,newdata=list(horsepower=hpGrid),se=TRUE)

#Compute bands on either side that is 2xSE

seBands=cbind(pred$fit+2*pred$se.fit,pred$fit-2*pred$se.fit)

#Plot the fit with Standard Error bands

plot(auto$horsepower,auto$mpg,xlim=hp,cex=.5,col="black",xlab="Horsepower",

ylab="MPG", main="Polynomial of degree 4")

lines(hpGrid,pred$fit,lwd=2,col="blue")

matlines(hpGrid,seBands,lwd=2,col="blue",lty=3)

1.1b Fit a 4th degree polynomial – Python code

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import os

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

from sklearn.preprocessing import PolynomialFeatures

from sklearn.linear_model import LinearRegression

#Read the auto data

autoDF =pd.read_csv("auto_mpg.csv",encoding="ISO-8859-1")

# Select columns

autoDF1=autoDF[['mpg','cylinder','displacement','horsepower','weight','acceleration','year']]

# Convert all columns to numeric

autoDF2 = autoDF1.apply(pd.to_numeric, errors='coerce')

#Drop NAs

autoDF3=autoDF2.dropna()

autoDF3.shape

X=autoDF3[['horsepower']]

y=autoDF3['mpg']

#Create a polynomial of degree 4

poly = PolynomialFeatures(degree=4)

X_poly = poly.fit_transform(X)

# Fit a polynomial regression line

linreg = LinearRegression().fit(X_poly, y)

# Create a range of values

hpGrid = np.arange(np.min(X),np.max(X),10)

hp=hpGrid.reshape(-1,1)

# Transform to 4th degree

poly = PolynomialFeatures(degree=4)

hp_poly = poly.fit_transform(hp)

#Create a scatter plot

plt.scatter(X,y)

# Fit the prediction

ypred=linreg.predict(hp_poly)

plt.title("Poylnomial of degree 4")

fig2=plt.xlabel("Horsepower")

fig2=plt.ylabel("MPG")

# Draw the regression curve

plt.plot(hp,ypred,c="red")

plt.savefig('fig1.png', bbox_inches='tight')

1.1c Fit a B-Spline – R Code

In the code below a B- Spline is fit to data. The B-spline requires the manual selection of knots

#Splines

library(splines)

# Fit a B-spline to the data. Select knots at 60,75,100,150

fit=lm(mpg~bs(horsepower,df=6,knots=c(60,75,100,150)),data=auto)

# Use the fitted regresion to predict

pred=predict(fit,newdata=list(horsepower=hpGrid),se=T)

# Create a scatter plot

plot(auto$horsepower,auto$mpg,xlim=hp,cex=.5,col="black",xlab="Horsepower",

ylab="MPG", main="B-Spline with 4 knots")

#Draw lines with 2 Standard Errors on either side

lines(hpGrid,pred$fit,lwd=2)

lines(hpGrid,pred$fit+2*pred$se,lty="dashed")

lines(hpGrid,pred$fit-2*pred$se,lty="dashed")

abline(v=c(60,75,100,150),lty=2,col="darkgreen")

1.1d Fit a Natural Spline – R Code

Here a ‘Natural Spline’ is used to fit .The Natural Spline extrapolates beyond the boundary knots and the ends of the function are much more constrained than a regular spline or a global polynomoial where the ends can wag a lot more. Natural splines do not require the explicit selection of knots

# There is no need to select the knots here. There is a smoothing parameter which

# can be specified by the degrees of freedom 'df' parameter. The natural spline

fit2=lm(mpg~ns(horsepower,df=4),data=auto)

pred=predict(fit2,newdata=list(horsepower=hpGrid),se=T)

plot(auto$horsepower,auto$mpg,xlim=hp,cex=.5,col="black",xlab="Horsepower",

ylab="MPG", main="Natural Splines")

lines(hpGrid,pred$fit,lwd=2)

lines(hpGrid,pred$fit+2*pred$se,lty="dashed")

lines(hpGrid,pred$fit-2*pred$se,lty="dashed")

1.1.e Fit a Smoothing Spline – R code

Here a smoothing spline is used. Smoothing splines also do not require the explicit setting of knots. We can change the ‘degrees of freedom(df)’ paramater to get the best fit

# Smoothing spline has a smoothing parameter, the degrees of freedom

# This is too wiggly

plot(auto$horsepower,auto$mpg,xlim=hp,cex=.5,col="black",xlab="Horsepower",

ylab="MPG", main="Smoothing Splines")

# Here df is set to 16. This has a lot of variance

fit=smooth.spline(auto$horsepower,auto$mpg,df=16)

lines(fit,col="red",lwd=2)

# We can use Cross Validation to allow the spline to pick the value of this smpopothing paramter. We do not need to set the degrees of freedom 'df'

fit=smooth.spline(auto$horsepower,auto$mpg,cv=TRUE)

lines(fit,col="blue",lwd=2)

1.1e Splines – Python

There isn’t as much treatment of splines in Python and SKLearn. I did find the LSQUnivariate, UnivariateSpline spline. The LSQUnivariate spline requires the explcit setting of knots

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import os

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from scipy.interpolate import LSQUnivariateSpline

autoDF =pd.read_csv("auto_mpg.csv",encoding="ISO-8859-1")

autoDF.shape

autoDF.columns

autoDF1=autoDF[['mpg','cylinder','displacement','horsepower','weight','acceleration','year']]

autoDF2 = autoDF1.apply(pd.to_numeric, errors='coerce')

auto=autoDF2.dropna()

auto=auto[['horsepower','mpg']].sort_values('horsepower')

# Set the knots manually

knots=[65,75,100,150]

# Create an array for X & y

X=np.array(auto['horsepower'])

y=np.array(auto['mpg'])

# Fit a LSQunivariate spline

s = LSQUnivariateSpline(X,y,knots)

#Plot the spline

xs = np.linspace(40,230,1000)

ys = s(xs)

plt.scatter(X, y)

plt.plot(xs, ys)

plt.savefig('fig2.png', bbox_inches='tight')

1.2 Generalized Additiive models (GAMs)

Generalized Additive Models (GAMs) is a really powerful ML tool.

In GAMs we use a different functions for each of the variables. GAMs give a much better fit since we can choose any function for the different sections

1.2a Generalized Additive Models (GAMs) – R Code

The plot below show the smooth spline that is fit for each of the features horsepower, cylinder, displacement, year and acceleration. We can use any function for example loess, 4rd order polynomial etc.

library(gam) # Fit a smoothing spline for horsepower, cyliner, displacement and acceleration gam=gam(mpg~s(horsepower,4)+s(cylinder,5)+s(displacement,4)+s(year,4)+s(acceleration,5),data=auto) # Display the summary of the fit. This give the significance of each of the paramwetr # Also an ANOVA is given for each combination of the features summary(gam) ## ## Call: gam(formula = mpg ~ s(horsepower, 4) + s(cylinder, 5) + s(displacement, ## 4) + s(year, 4) + s(acceleration, 5), data = auto) ## Deviance Residuals: ## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max ## -8.3190 -1.4436 -0.0261 1.2279 12.0873 ## ## (Dispersion Parameter for gaussian family taken to be 6.9943) ## ## Null Deviance: 23818.99 on 391 degrees of freedom ## Residual Deviance: 2587.881 on 370 degrees of freedom ## AIC: 1898.282 ## ## Number of Local Scoring Iterations: 3 ## ## Anova for Parametric Effects ## Df Sum Sq Mean Sq F value Pr(>F) ## s(horsepower, 4) 1 15632.8 15632.8 2235.085 < 2.2e-16 *** ## s(cylinder, 5) 1 508.2 508.2 72.666 3.958e-16 *** ## s(displacement, 4) 1 374.3 374.3 53.514 1.606e-12 *** ## s(year, 4) 1 2263.2 2263.2 323.583 < 2.2e-16 *** ## s(acceleration, 5) 1 372.4 372.4 53.246 1.809e-12 *** ## Residuals 370 2587.9 7.0 ## --- ## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1 ## ## Anova for Nonparametric Effects ## Npar Df Npar F Pr(F) ## (Intercept) ## s(horsepower, 4) 3 13.825 1.453e-08 *** ## s(cylinder, 5) 3 17.668 9.712e-11 *** ## s(displacement, 4) 3 44.573 < 2.2e-16 *** ## s(year, 4) 3 23.364 7.183e-14 *** ## s(acceleration, 5) 4 3.848 0.004453 ** ## --- ## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1 par(mfrow=c(2,3)) plot(gam,se=TRUE)

1.2b Generalized Additive Models (GAMs) – Python Code

I did not find the equivalent of GAMs in SKlearn in Python. There was an early prototype (2012) in Github. Looks like it is still work in progress or has probably been abandoned.

1.3 Tree based Machine Learning Models

Tree based Machine Learning are all based on the ‘bootstrapping’ technique. In bootstrapping given a sample of size N, we create datasets of size N by sampling this original dataset with replacement. Machine Learning models are built on the different bootstrapped samples and then averaged.

Decision Trees as seen above have the tendency to overfit. There are several techniques that help to avoid this namely a) Bagging b) Random Forests c) Boosting

Bagging, Random Forest and Gradient Boosting

Bagging: Bagging, or Bootstrap Aggregation decreases the variance of predictions, by creating separate Decisiion Tree based ML models on the different samples and then averaging these ML models

Random Forests: Bagging is a greedy algorithm and tries to produce splits based on all variables which try to minimize the error. However the different ML models have a high correlation. Random Forests remove this shortcoming, by using a variable and random set of features to split on. Hence the features chosen and the resulting trees are uncorrelated. When these ML models are averaged the performance is much better.

Boosting: Gradient Boosted Decision Trees also use an ensemble of trees but they don’t build Machine Learning models with random set of features at each step. Rather small and simple trees are built. Successive trees try to minimize the error from the earlier trees.

Out of Bag (OOB) Error: In Random Forest and Gradient Boosting for each bootstrap sample taken from the dataset, there will be samples left out. These are known as Out of Bag samples.Classification accuracy carried out on these OOB samples is known as OOB error

1.31a Decision Trees – R Code

The code below creates a Decision tree with the cancer training data. The summary of the fit is output. Based on the ML model, the predict function is used on test data and a confusion matrix is output.

# Read the cancer data

library(tree)

library(caret)

library(e1071)

cancer <- read.csv("cancer.csv",stringsAsFactors = FALSE)

cancer <- cancer[,2:32]

cancer$target <- as.factor(cancer$target)

train_idx <- trainTestSplit(cancer,trainPercent=75,seed=5)

train <- cancer[train_idx, ]

test <- cancer[-train_idx, ]

# Create Decision Tree

cancerStatus=tree(target~.,train)

summary(cancerStatus)

##

## Classification tree:

## tree(formula = target ~ ., data = train)

## Variables actually used in tree construction:

## [1] "worst.perimeter" "worst.concave.points" "area.error"

## [4] "worst.texture" "mean.texture" "mean.concave.points"

## Number of terminal nodes: 9

## Residual mean deviance: 0.1218 = 50.8 / 417

## Misclassification error rate: 0.02347 = 10 / 426

pred <- predict(cancerStatus,newdata=test,type="class")

confusionMatrix(pred,test$target)

## Confusion Matrix and Statistics

##

## Reference

## Prediction 0 1

## 0 49 7

## 1 8 78

##

## Accuracy : 0.8944

## 95% CI : (0.8318, 0.9397)

## No Information Rate : 0.5986

## P-Value [Acc > NIR] : 4.641e-15

##

## Kappa : 0.7795

## Mcnemar's Test P-Value : 1

##

## Sensitivity : 0.8596

## Specificity : 0.9176

## Pos Pred Value : 0.8750

## Neg Pred Value : 0.9070

## Prevalence : 0.4014

## Detection Rate : 0.3451

## Detection Prevalence : 0.3944

## Balanced Accuracy : 0.8886

##

## 'Positive' Class : 0

##

# Plot decision tree with labels

plot(cancerStatus)

text(cancerStatus,pretty=0)

1.31b Decision Trees – Cross Validation – R Code

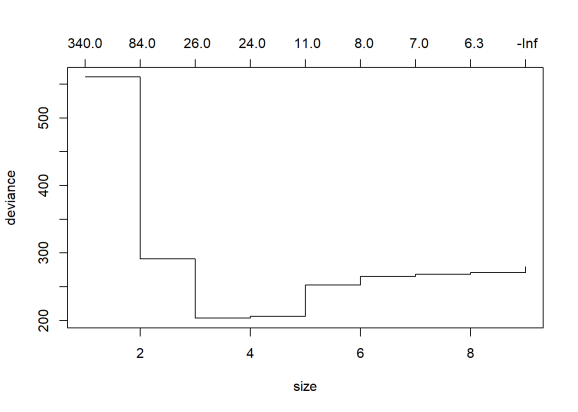

We can also perform a Cross Validation on the data to identify the Decision Tree which will give the minimum deviance.

library(tree)

cancer <- read.csv("cancer.csv",stringsAsFactors = FALSE)

cancer <- cancer[,2:32]

cancer$target <- as.factor(cancer$target)

train_idx <- trainTestSplit(cancer,trainPercent=75,seed=5)

train <- cancer[train_idx, ]

test <- cancer[-train_idx, ]

# Create Decision Tree

cancerStatus=tree(target~.,train)

# Execute 10 fold cross validation

cvCancer=cv.tree(cancerStatus)

plot(cvCancer)

# Plot the plot(cvCancer$size,cvCancer$dev,type='b')

prunedCancer=prune.tree(cancerStatus,best=4) plot(prunedCancer) text(prunedCancer,pretty=0)

pred <- predict(prunedCancer,newdata=test,type="class") confusionMatrix(pred,test$target) ## Confusion Matrix and Statistics ## ## Reference ## Prediction 0 1 ## 0 50 7 ## 1 7 78 ## ## Accuracy : 0.9014 ## 95% CI : (0.8401, 0.945) ## No Information Rate : 0.5986 ## P-Value [Acc > NIR] : 7.988e-16 ## ## Kappa : 0.7948 ## Mcnemar's Test P-Value : 1 ## ## Sensitivity : 0.8772 ## Specificity : 0.9176 ## Pos Pred Value : 0.8772 ## Neg Pred Value : 0.9176 ## Prevalence : 0.4014 ## Detection Rate : 0.3521 ## Detection Prevalence : 0.4014 ## Balanced Accuracy : 0.8974 ## ## 'Positive' Class : 0 ##

1.31c Decision Trees – Python Code

Below is the Python code for creating Decision Trees. The accuracy, precision, recall and F1 score is computed on the test data set.

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import os

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from sklearn.metrics import confusion_matrix

from sklearn import tree

from sklearn.datasets import load_breast_cancer

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

from sklearn.tree import DecisionTreeClassifier

from sklearn.datasets import make_classification, make_blobs

from sklearn.metrics import accuracy_score, precision_score, recall_score, f1_score

import graphviz

cancer = load_breast_cancer()

(X_cancer, y_cancer) = load_breast_cancer(return_X_y = True)

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X_cancer, y_cancer,

random_state = 0)

clf = DecisionTreeClassifier().fit(X_train, y_train)

print('Accuracy of Decision Tree classifier on training set: {:.2f}'

.format(clf.score(X_train, y_train)))

print('Accuracy of Decision Tree classifier on test set: {:.2f}'

.format(clf.score(X_test, y_test)))

y_predicted=clf.predict(X_test)

confusion = confusion_matrix(y_test, y_predicted)

print('Accuracy: {:.2f}'.format(accuracy_score(y_test, y_predicted)))

print('Precision: {:.2f}'.format(precision_score(y_test, y_predicted)))

print('Recall: {:.2f}'.format(recall_score(y_test, y_predicted)))

print('F1: {:.2f}'.format(f1_score(y_test, y_predicted)))

# Plot the Decision Tree

clf = DecisionTreeClassifier(max_depth=2).fit(X_train, y_train)

dot_data = tree.export_graphviz(clf, out_file=None,

feature_names=cancer.feature_names,

class_names=cancer.target_names,

filled=True, rounded=True,

special_characters=True)

graph = graphviz.Source(dot_data)

graph

## Accuracy of Decision Tree classifier on training set: 1.00

## Accuracy of Decision Tree classifier on test set: 0.87

## Accuracy: 0.87

## Precision: 0.97

## Recall: 0.82

## F1: 0.89

1.31d Decision Trees – Cross Validation – Python Code

In the code below 5-fold cross validation is performed for different depths of the tree and the accuracy is computed. The accuracy on the test set seems to plateau when the depth is 8. But it is seen to increase again from 10 to 12. More analysis needs to be done here

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import os

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from sklearn.datasets import load_breast_cancer

from sklearn.tree import DecisionTreeClassifier

(X_cancer, y_cancer) = load_breast_cancer(return_X_y = True)

from sklearn.cross_validation import train_test_split, KFold

def computeCVAccuracy(X,y,folds):

accuracy=[]

foldAcc=[]

depth=[1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12]

nK=len(X)/float(folds)

xval_err=0

for i in depth:

kf = KFold(len(X),n_folds=folds)

for train_index, test_index in kf:

X_train, X_test = X.iloc[train_index], X.iloc[test_index]

y_train, y_test = y.iloc[train_index], y.iloc[test_index]

clf = DecisionTreeClassifier(max_depth = i).fit(X_train, y_train)

score=clf.score(X_test, y_test)

accuracy.append(score)

foldAcc.append(np.mean(accuracy))

return(foldAcc)

cvAccuracy=computeCVAccuracy(pd.DataFrame(X_cancer),pd.DataFrame(y_cancer),folds=10)

df1=pd.DataFrame(cvAccuracy)

df1.columns=['cvAccuracy']

df=df1.reindex([1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12])

df.plot()

plt.title("Decision Tree - 10-fold Cross Validation Accuracy vs Depth of tree")

plt.xlabel("Depth of tree")

plt.ylabel("Accuracy")

plt.savefig('fig3.png', bbox_inches='tight')

1.4a Random Forest – R code

A Random Forest is fit using the Boston data. The summary shows that 4 variables were randomly chosen at each split and the resulting ML model explains 88.72% of the test data. Also the variable importance is plotted. It can be seen that ‘rooms’ and ‘status’ are the most influential features in the model

library(randomForest)

df=read.csv("Boston.csv",stringsAsFactors = FALSE) # Data from MASS - SL

# Select specific columns

Boston <- df %>% dplyr::select("crimeRate","zone","indus","charles","nox","rooms","age", "distances","highways","tax","teacherRatio","color",

"status","medianValue")

# Fit a Random Forest on the Boston training data

rfBoston=randomForest(medianValue~.,data=Boston)

# Display the summatu of the fit. It can be seen that the MSE is 10.88

# and the percentage variance explained is 86.14%. About 4 variables were tried at each # #split for a maximum tree of 500.

# The MSE and percent variance is on Out of Bag trees

rfBoston

##

## Call:

## randomForest(formula = medianValue ~ ., data = Boston)

## Type of random forest: regression

## Number of trees: 500

## No. of variables tried at each split: 4

##

## Mean of squared residuals: 9.521672

## % Var explained: 88.72

#List and plot the variable importances

importance(rfBoston)

## IncNodePurity

## crimeRate 2602.1550

## zone 258.8057

## indus 2599.6635

## charles 240.2879

## nox 2748.8485

## rooms 12011.6178

## age 1083.3242

## distances 2432.8962

## highways 393.5599

## tax 1348.6987

## teacherRatio 2841.5151

## color 731.4387

## status 12735.4046

varImpPlot(rfBoston)

1.4b Random Forest-OOB and Cross Validation Error – R code

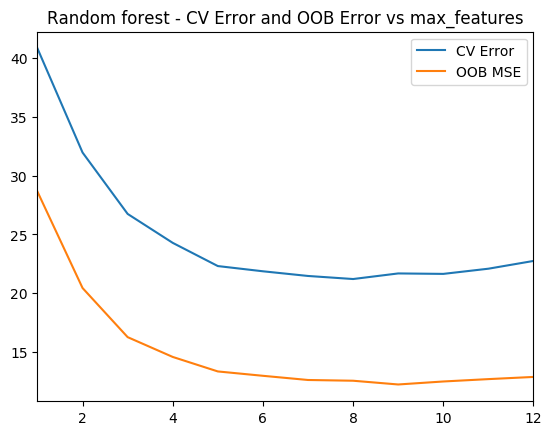

The figure below shows the OOB error and the Cross Validation error vs the ‘mtry’. Here mtry indicates the number of random features that are chosen at each split. The lowest test error occurs when mtry = 8

library(randomForest)

df=read.csv("Boston.csv",stringsAsFactors = FALSE) # Data from MASS - SL

# Select specific columns

Boston <- df %>% dplyr::select("crimeRate","zone","indus","charles","nox","rooms","age", "distances","highways","tax","teacherRatio","color",

"status","medianValue")

# Split as training and tst sets

train_idx <- trainTestSplit(Boston,trainPercent=75,seed=5)

train <- Boston[train_idx, ]

test <- Boston[-train_idx, ]

#Initialize OOD and testError

oobError <- NULL

testError <- NULL

# In the code below the number of variables to consider at each split is increased

# from 1 - 13(max features) and the OOB error and the MSE is computed

for(i in 1:13){

fitRF=randomForest(medianValue~.,data=train,mtry=i,ntree=400)

oobError[i] <-fitRF$mse[400]

pred <- predict(fitRF,newdata=test)

testError[i] <- mean((pred-test$medianValue)^2)

}

# We can see the OOB and Test Error. It can be seen that the Random Forest performs

# best with the lowers MSE at mtry=6

matplot(1:13,cbind(testError,oobError),pch=19,col=c("red","blue"),

type="b",xlab="mtry(no of varaibles at each split)", ylab="Mean Squared Error",

main="Random Forest - OOB and Test Error")

legend("topright",legend=c("OOB","Test"),pch=19,col=c("red","blue"))

1.4c Random Forest – Python code

The python code for Random Forest Regression is shown below. The training and test score is computed. The variable importance shows that ‘rooms’ and ‘status’ are the most influential of the variables

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import os

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

from sklearn.ensemble import RandomForestRegressor

df = pd.read_csv("Boston.csv",encoding = "ISO-8859-1")

X=df[['crimeRate','zone', 'indus','charles','nox','rooms', 'age','distances','highways','tax',

'teacherRatio','color','status']]

y=df['medianValue']

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y, random_state = 0)

regr = RandomForestRegressor(max_depth=4, random_state=0)

regr.fit(X_train, y_train)

print('R-squared score (training): {:.3f}'

.format(regr.score(X_train, y_train)))

print('R-squared score (test): {:.3f}'

.format(regr.score(X_test, y_test)))

feature_names=['crimeRate','zone', 'indus','charles','nox','rooms', 'age','distances','highways','tax',

'teacherRatio','color','status']

print(regr.feature_importances_)

plt.figure(figsize=(10,6),dpi=80)

c_features=X_train.shape[1]

plt.barh(np.arange(c_features),regr.feature_importances_)

plt.xlabel("Feature importance")

plt.ylabel("Feature name")

plt.yticks(np.arange(c_features), feature_names)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.savefig('fig4.png', bbox_inches='tight')

## R-squared score (training): 0.917

## R-squared score (test): 0.734

## [ 0.03437382 0. 0.00580335 0. 0.00731004 0.36461548

## 0.00638577 0.03432173 0.0041244 0.01732328 0.01074148 0.0012638

## 0.51373683]

1.4d Random Forest – Cross Validation and OOB Error – Python code

As with R the ‘max_features’ determines the random number of features the random forest will use at each split. The plot shows that when max_features=8 the MSE is lowest

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import os

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

from sklearn.ensemble import RandomForestRegressor

from sklearn.model_selection import cross_val_score

df = pd.read_csv("Boston.csv",encoding = "ISO-8859-1")

X=df[['crimeRate','zone', 'indus','charles','nox','rooms', 'age','distances','highways','tax',

'teacherRatio','color','status']]

y=df['medianValue']

cvError=[]

oobError=[]

oobMSE=[]

for i in range(1,13):

regr = RandomForestRegressor(max_depth=4, n_estimators=400,max_features=i,oob_score=True,random_state=0)

mse= np.mean(cross_val_score(regr, X, y, cv=5,scoring = 'neg_mean_squared_error'))

# Since this is neg_mean_squared_error I have inverted the sign to get MSE

cvError.append(-mse)

# Fit on all data to compute OOB error

regr.fit(X, y)

# Record the OOB error for each `max_features=i` setting

oob = 1 - regr.oob_score_

oobError.append(oob)

# Get the Out of Bag prediction

oobPred=regr.oob_prediction_

# Compute the Mean Squared Error between OOB Prediction and target

mseOOB=np.mean(np.square(oobPred-y))

oobMSE.append(mseOOB)

# Plot the CV Error and OOB Error

# Set max_features

maxFeatures=np.arange(1,13)

cvError=pd.DataFrame(cvError,index=maxFeatures)

oobMSE=pd.DataFrame(oobMSE,index=maxFeatures)

#Plot

fig8=df.plot()

fig8=plt.title('Random forest - CV Error and OOB Error vs max_features')

fig8.figure.savefig('fig8.png', bbox_inches='tight')

#Plot the OOB Error vs max_features

plt.plot(range(1,13),oobError)

fig2=plt.title("Random Forest - OOB Error vs max_features (variable no of features)")

fig2=plt.xlabel("max_features (variable no of features)")

fig2=plt.ylabel("OOB Error")

fig2.figure.savefig('fig7.png', bbox_inches='tight')

1.5a Boosting – R code

Here a Gradient Boosted ML Model is built with a n.trees=5000, with a learning rate of 0.01 and depth of 4. The feature importance plot also shows that rooms and status are the 2 most important features. The MSE vs the number of trees plateaus around 2000 trees

library(gbm)

# Perform gradient boosting on the Boston data set. The distribution is gaussian since we

# doing MSE. The interaction depth specifies the number of splits

boostBoston=gbm(medianValue~.,data=train,distribution="gaussian",n.trees=5000,

shrinkage=0.01,interaction.depth=4)

#The summary gives the variable importance. The 2 most significant variables are

# number of rooms and lower status

summary(boostBoston)

## var rel.inf ## rooms rooms 42.2267200 ## status status 27.3024671 ## distances distances 7.9447972 ## crimeRate crimeRate 5.0238827 ## nox nox 4.0616548 ## teacherRatio teacherRatio 3.1991999 ## age age 2.7909772 ## color color 2.3436295 ## tax tax 2.1386213 ## charles charles 1.3799109 ## highways highways 0.7644026 ## indus indus 0.7236082 ## zone zone 0.1001287 # The plots below show how each variable relates to the median value of the home. As # the number of roomd increase the median value increases and with increase in lower status # the median value decreases par(mfrow=c(1,2)) #Plot the relation between the top 2 features and the target plot(boostBoston,i="rooms") plot(boostBoston,i="status")

# Create a sequence of trees between 100-5000 incremented by 50

nTrees=seq(100,5000,by=50)

# Predict the values for the test data

pred <- predict(boostBoston,newdata=test,n.trees=nTrees)

# Compute the mean for each of the MSE for each of the number of trees

boostError <- apply((pred-test$medianValue)^2,2,mean)

#Plot the MSE vs the number of trees

plot(nTrees,boostError,pch=19,col="blue",ylab="Mean Squared Error",

main="Boosting Test Error")

1.5b Cross Validation Boosting – R code

Included below is a cross validation error vs the learning rate. The lowest error is when learning rate = 0.09

cvError <- NULL

s <- c(.001,0.01,0.03,0.05,0.07,0.09,0.1)

for(i in seq_along(s)){

cvBoost=gbm(medianValue~.,data=train,distribution="gaussian",n.trees=5000,

shrinkage=s[i],interaction.depth=4,cv.folds=5)

cvError[i] <- mean(cvBoost$cv.error)

}

# Create a data frame for plotting

a <- rbind(s,cvError)

b <- as.data.frame(t(a))

# It can be seen that a shrinkage parameter of 0,05 gives the lowes CV Error

ggplot(b,aes(s,cvError)) + geom_point() + geom_line(color="blue") +

xlab("Shrinkage") + ylab("Cross Validation Error") +

ggtitle("Gradient boosted trees - Cross Validation error vs Shrinkage")

1.5c Boosting – Python code

A gradient boost ML model in Python is created below. The Rsquared score is computed on the training and test data.

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import os

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

from sklearn.ensemble import GradientBoostingRegressor

df = pd.read_csv("Boston.csv",encoding = "ISO-8859-1")

X=df[['crimeRate','zone', 'indus','charles','nox','rooms', 'age','distances','highways','tax',

'teacherRatio','color','status']]

y=df['medianValue']

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y, random_state = 0)

regr = GradientBoostingRegressor()

regr.fit(X_train, y_train)

print('R-squared score (training): {:.3f}'

.format(regr.score(X_train, y_train)))

print('R-squared score (test): {:.3f}'

.format(regr.score(X_test, y_test)))

## R-squared score (training): 0.983

## R-squared score (test): 0.821

1.5c Cross Validation Boosting – Python code

the cross validation error is computed as the learning rate is varied. The minimum CV eror occurs when lr = 0.04

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import os

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

from sklearn.ensemble import RandomForestRegressor

from sklearn.ensemble import GradientBoostingRegressor

from sklearn.model_selection import cross_val_score

df = pd.read_csv("Boston.csv",encoding = "ISO-8859-1")

X=df[['crimeRate','zone', 'indus','charles','nox','rooms', 'age','distances','highways','tax',

'teacherRatio','color','status']]

y=df['medianValue']

cvError=[]

learning_rate =[.001,0.01,0.03,0.05,0.07,0.09,0.1]

for lr in learning_rate:

regr = GradientBoostingRegressor(max_depth=4, n_estimators=400,learning_rate =lr,random_state=0)

mse= np.mean(cross_val_score(regr, X, y, cv=10,scoring = 'neg_mean_squared_error'))

# Since this is neg_mean_squared_error I have inverted the sign to get MSE

cvError.append(-mse)

learning_rate =[.001,0.01,0.03,0.05,0.07,0.09,0.1]

plt.plot(learning_rate,cvError)

plt.title("Gradient Boosting - 5-fold CV- Mean Squared Error vs max_features (variable no of features)")

plt.xlabel("max_features (variable no of features)")

plt.ylabel("Mean Squared Error")

plt.savefig('fig6.png', bbox_inches='tight')

Conclusion This post covered Splines and Tree based ML models like Bagging, Random Forest and Boosting. Stay tuned for further updates.

You may also like

- Re-introducing cricketr! : An R package to analyze performances of cricketer

- Designing a Social Web Portal

- My travels through the realms of Data Science, Machine Learning, Deep Learning and (AI)

- My TEDx talk on the “Internet of Things”

- Singularity

- A closer look at “Robot Horse on a Trot” in Android

To see all posts see Index of posts

R-bloggers.com offers daily e-mail updates about R news and tutorials about learning R and many other topics. Click here if you're looking to post or find an R/data-science job.

Want to share your content on R-bloggers? click here if you have a blog, or here if you don't.