Tidying and Analysing Response Time Data Using R

Want to share your content on R-bloggers? click here if you have a blog, or here if you don't.

You have spent months collecting data, some participants turn up on time, some participants turn up late, and others do not show up at all. After all this, all you want to do is get down to analysing your data and writing up your results. However, before you do all that, you need to extract all the information you need from the output of your experiment. Until the last few weeks, the process of tidying my data took me around 10 minutes per participant as I would do it all manually through Excel. Even for a moderate sample size, this starts to take up a large chunk of time that could be spent doing other things like writing or having a beer. Inspired by the book ‘Python for experimental psychologists’ by Edwin Dalmaijer (which I recommend you buy if you are interested in learning about programming in psychology), I started to think how I could use R to do all the hard work for me. Hopefully this post will allow you to see how you can do this in R and be able to create your own data tidying script.

The example that I am using is a measure of attentional bias known as the dot probe task. The participant is presented with two cues, and when they disappear a small dot appears in the location of one of the cues. The participant has to provide a keyboard response to whether the cue is on the left or right. The idea behind the task is that if participants provide a faster response on average to a particular type of cue, it is assumed that their attention is already in the location of the cue. In this particular example, there are two within-subject IVs which are the stimulus response asynchrony (SOA or the duration the stimuli are presented on the screen for) and trial type. SOA has three levels which are whether the cues are presented for 200ms, 500ms, or 2000ms. Trial type has two levels for whether the dot probe replaces either a smoking or a neutral cue.

If we were to do this process manually, we would split it up into several stages. Firstly, we need to load the data file up so that we can see it. Secondly, we want to only analyse correct responses. Thirdly, we want to remove any extreme values. Finally, we want to calculate the averages for each condition in the experiment.

Step one: importing the data file

For the script to work later on, we need to install some packages. I am a big fan of the tidyverse series of packages developed by Hadley Wickham and colleagues for data science. Therefore all of the packages we will be using can be imported using the tidyverse package. If you do not have this installed, you will need to do this first using the install.packages() function (e.g. install.packages(“tidyverse”) ).

Most experimental software will provide you with a spreadsheet of your data, and after you make sure this is a .csv file we want to import the data so that we can toy around with it. If you want to follow along with the example, you can find an example data set and the full R script on Github.

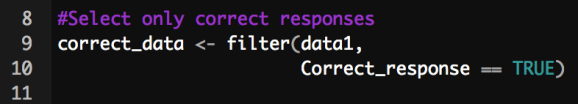

Step two: selecting correct responses

In behavioural experiments, it is standard practise to only analyse correct trials. When you design the experiment, you usually indicate which response is correct so that the software can code whether the response the participant provided was correct or not. This is usually in the form of a 1 for a correct response and a 0 for an incorrect response. We can take advantage of R reading this as a logical value and only select the data rows that are coded 1 (which is interpreted as TRUE in R):

Step three: remove extreme responses

Now that we have only correct responses, we can start to worry about whether these responses fall within our predefined boundaries. An important point to note here is that these boundaries can be quite controversial and is it crucial that they are set in advance. The boundaries for this example are within 200ms and 2000ms. To remove any additional extreme responses, any values that are above 3 standard deviations of the mean are also removed. I know this strategy is not perfect but I was sticking with the previous literature here. You can use your own boundaries that you have decided for your own data. In this part of the script, we are starting to take advantage of piping (%>%) to string several functions together. The following code first selects only response times that are within 200ms and 2000ms, then removes any additional extreme responses that are above 3 standard deviations of the mean:

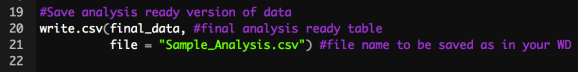

We have now finished with tidying the data up and I like to save this version of the data file for if I ever want to come back to it later without having to repeat the previous steps:

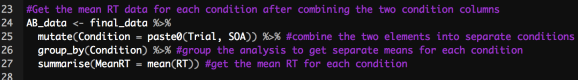

Step four: calculate the mean values for each condition

At the beginning of this post, I explained that there was two within-subject IVs: one with two levels and one with three levels. This leaves us with six conditions that we want to know the average response time for. Therefore, to calculate each average we want to analyse the data for each combination of SOA and trial. We can again take advantage of the piping in the tidyverse and combine several functions together. We can create a new column called Condition using the mutate and paste0 functions to combine the Trial and SOA values together. We can then use the group_by and summarise functions to leave us with a mean response time for each condition:

Step five: save the mean RTs in a table

The previous step left us with a final table called AB_data. This contains the mean response times for each of the six combinations of Trial and SOA. We can again save this table for future reference, and we can now use it to record each mean into a master spreadsheet that contains the rest of your participants’ data:

Hopefully you will be able to use this template for your own data analysis by changing the steps to suite your own experimental conditions. If you want any suggestions for how to write a script for your own experiment, feel free to comment. I would like to thank everyone on the Psychological Methods Discussion Group on Facebook who commented on a previous version of this post. I was able to make it much more efficient and halved the size of the original script with their helpful comments. Go peer review!

R-bloggers.com offers daily e-mail updates about R news and tutorials about learning R and many other topics. Click here if you're looking to post or find an R/data-science job.

Want to share your content on R-bloggers? click here if you have a blog, or here if you don't.